Roger Cooper

(1939 – 2020)

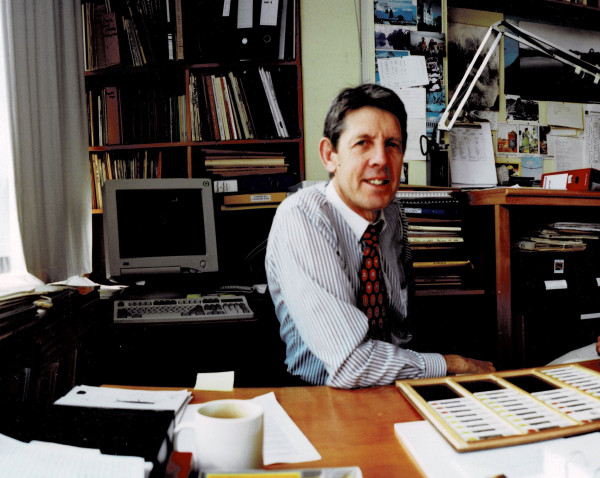

Dr Roger Cooper in 1988

(12 March 1939 – 2 March 2020)

Dr Roger Cooper FRSNZ passed away on 2nd March, 2020, following a battle with cancer. Roger was one of New Zealand’s pre-eminent paleontologists. His contributions to our understanding of Zealandia’s rich geological and paleontological histories are enormous and he leaves an important corpus of local and international research. His life was rich: accounts of his career read like something from a child’s adventure story and open a window on explorative, frontier-style field research that is now almost a thing of the past. He was an insightful, gentle, generous and kind colleague and mentor, and a person of great integrity. He was, quite simply, one of the best.

Roger grew up in Eastbourne, the seaside village suburb of Lower Hutt, located on the eastern shore of Port Nicholson (Wellington Harbour). The son of Lawrence and Roslyn Cooper (nee Sherman), he was the second eldest of five children. His parents met in 1933 on a ship to the UK, when Lawrie was starting his OE and Ros was leaving Burma, where she had grown up. Eastbourne in the 1940s afforded ready access to waters of the harbour and the steep, bush-clad hills fringing the village, and adventure for the children was never far away. The Pencarrow coast track to the south was one of Roger’s favourites, and site of a secret valley where he and his father boiled billies and, later, Roger camped with his own family. Other adventures for Roger lay in the garden shed and presaged use of a rock hammer – once, his father found Roger hammering a live .303 cartridge in the vice to see what would happen, and at other times the young paleontologist hammered holes in the lids of his father’s home brew in order to test the contents. As a child and young man, Roger was a passionate Meccano fan and woodworker – some of his furniture creations are still used by his brother Nigel. He was also a committed Wolf Cub, head prefect at Muritai School, tramper and cricketer. On the subject of cricket, Roger recalled that the small lawn of his childhood home was squeezed between beach and home, and he attributed his life-long weakness of cricket leg-side strokes to the fact that these resulted in broken windows and were strongly discouraged; despite this, he was an opening batsman for Hutt Valley High School’s 1st XI.

As a geology student at Victoria University of Wellington, one of Roger’s first paid tasks was in January 1960, as field assistant to Gerald Lensen of the Geological Survey, who was making the original 1:250,000 geological map of Marlborough. The trip lasted almost three months and was an incredible learning experience for the second-year student. Along with Mike Hall and Tom Haskell, also student assistants, three pack horses, military radios, and rifles, they wound their way into the Clarence valley after stints in the Awatere valley and on the coast. A dislocated shoulder, acquired using a rock hammer as an “ice axe” on steep scree, meant that Gerald had to go out for treatment, and for much of the time in the Clarence, the three students were on their own. The area is remote and other humans encountered were mainly deer cullers more used to the company of themselves and their dogs. The beautiful and well-provisioned cob cottage at Quail Flat was a welcome oasis, complete with outdoor, wood-fired bread oven and a radio that worked (their military radios having proven useless). Roger recalled that, in a lovely juxtaposition, the BBC news on the night that they arrived announced both the birth of Prince Andrew and the invention of the contraceptive pill. A scheduled air drop of provisions was only partially successful – the provisions did indeed drop, but the contents of the carefully packed and straw-padded sugar sacks were distributed over a large area of river flats, and pervaded by honey, having been despatched from a great height, at great speed, by the pilot. The horses were a mixed blessing, but this did not stop the party from wrangling and semi-taming a half-wild stallion. Things came to a head when one of the cantankerous mares bolted, with cameras, film and completed field maps on her back; a split-second decision by the geologist holding the rifle resulted in a £40 bill from the farmer to the Geological Survey for one “very valuable” horse.

The following summer, Roger swapped the heat of inland Marlborough for ice, as a student member of the Victoria University Antarctic Expedition (VUWAE 5). This took him to the western margin of the Koettlitz Glacier and the flanks of the South Victoria Range. For two months his job was to make a geological map of the region as the party tramped between base camps and food dumps that had been deposited by helicopter. One of the food dumps almost resulted in catastrophe, as the aging helicopter hit the snow in a saddle but, remarkably, bounced and continued flying. Other dramas followed. Roger recalled the angst and profound isolation of crossing a large glacier in total whiteout – unable to see even one’s own feet – the five party members navigating by compass, linked by rope and ready to plunge their ice axes into the snow should the rope suddenly run, indicating that one of them had fallen into a crevasse. On Christmas Day, working as usual, two members of the party found flowing water, the result of a breached ice dam at the snout of a glacier. Boxing Day was spent by the entire party building a “scientific” dam and then swimming; Roger always supposed that this was the first swim in a flowing river in the Ross Dependency. In typical New Zealand style, the expedition had begged and borrowed much of their equipment, and lived in woollen clothing, carrying everything in old Mountain Mule packs. Camera film, rolling tobacco and liqueur were donated by Wellington companies. Most of the time, meals comprised “white powder, grey powder, yellow powder” (milk, potato, egg) that were mixed with water and cooked. In later years Roger returned to the Antarctic twice, leading expeditions in 1974-5 and 1981-2. During these expeditions, the parties produced geological maps and made important fossil collections that have clarified the geological history of Antarctica and its relationships to the other continental fragments of the great southern supercontinent Gondwana.

During 1961, Roger completed his BSc Honours at Victoria University. Unbeknownst (perhaps) to university authorities, he lived for two months in the old green sheds that used to house the Geology Department, with a sleeping bag under a work bench and his primus above. Later, he was to share a famous student flat with a number of notable geologists – James Kennett, Tom Haskell and Jim Eade. The following summer, Roger accompanied several other students (including one of us: AGB) and the Wellman family for a geological tour of north-western Nelson, and it was during this trip that Roger’s MSc topic – the Ordovician and Silurian in the region of the Pikikiruna Range – was identified. Upon completing his MSc, he spent a year mapping areas of commercially useful limestone in Otago and Southland for the New Zealand Geological Survey. His MSc research set the course for much of his subsequent career, but before starting his PhD, he embarked on a rather different enterprise.

Starting in March 1963, Roger undertook an eighteen-month United Nations contract in Sabah, Borneo. The Labuk Valley Project was designed to investigate resources needed to support local industry in the lowlands and thereby encourage the hill tribes to resettle, so that they would have access to modern medicine, education, etc. The project involved geochemical sampling traverses in remote areas, lasting a week to ten days at a time, with transport by canoe and then by foot through the jungle. Assistance in the jungle camps and on the traverses was provided by Iban people; they travelled without shoes, carried large weights on their backs in sheet-iron boxes, were highly skilled in jungle lore, expert navigators, and careful to protect Roger from harm. The young geologist shared the “tent” – a fly sheet draped over a pole – with the Ibans, conversed with them in Bazaar Malay, and greatly enjoyed these traverses. Throughout his later field work in New Zealand, Roger used the parang – the jungle knife forged by hand from the leaf spring of a car – that was gifted to him by his jungle minders (the blowpipe, on the other hand, was used only for entertainment in New Zealand). Roger’s early plans to live off tinned meat whilst in the jungle resulted in vitamin deficiency and saw him eat thereafter with the Iban: on the jungle traverses, they lived largely off the land, eating land turtle, fish, mouse deer, snake, monkeys, fungus, berries, and bark, all accompanied by rice. Wildlife was a constant source of interest and irritation, in equal measure – fire ants, enormous spiders and leeches, gibbons whooping and swinging through the trees, hornbills, geckos, giant pythons up to seven metres long, and other snakes such as a green whip snake that became Roger’s ill-tempered pet for a short time. Again, there was near disaster involving a small aircraft, when they became trapped above thick cloud that was surrounding unseen mountains; eventually the pilot flew the plane down in a tremendously steep spiral through a small hole in the clouds, levelling out just above glimpses of ground. As if such adventures weren’t enough, Roger teamed up with another expatriate for explorations using borrowed scrambler motorbikes; the highlight of these trips was along an abandoned and, to all intents impassable, former wartime track across the Crocker Range to the foot of Mt Kinabalu. Bouncing the bikes over fallen trees, walking them through bogs, and at one point carrying them over a large slip with the help of bemused locals, eventually the benighted travellers had an unplanned stay with a local hill tribesman in his shanty. Late in 1963, Roger was joined in Borneo by his then wife Dot – they had married just ten days before he had first departed for the contract, and she then worked at the Geological Survey in the town of Jesselton (now Kota Kinabalu) whilst Roger was away on his jungle traverses. Together they continued to explore the west coast of Borneo, and climbed Mt Kinabalu (4095 m). Recently, in 2018, Roger returned to Borneo with his second wife, Robyn, and managed to reconnect with some of the families he had known there in 1963-4.

Later, Roger’s recreational adventures continued with Robyn: they climbed Mt Vesuvius during one of several archaeological trips to Turkey and the Middle East, experienced hot-air ballooning in white-out over Cappadocia, tramped around Lord Howe island, and explored his mother’s old haunts in Burma, being guided in her hometown of Maymyo by the family who bought the property from Roger’s grandmother in 1933 and still live there.

During his MSc research, Roger had become interested in evolution of a particular fossil graptolite species, Isograptus caduceus; graptolites are an ancient group of animals, now extinct, that floated in the oceans and dominated marine ecosystems about 400-500 million years ago. Upon return from Borneo, he embarked on a PhD at Victoria University to study these fossils, supervised by Harold Wellman and Paul Vella. The senior geology students had their offices in an old house at 11 Clermont Terrace, about a kilometre from the main university Kelburn campus. Harold and Paul usually joined the students for lunch, and Harold – famously argumentative – typically would have dreamed up a topic for “discussion”, often not geological, and so the problems of the world were solved, one by one, as toast burnt on the ancient gas stove. One of us who shared that house (AGB) remembers this as a wonderfully enjoyable time of life. Roger’s thesis was examined in 1969 by the famous Woodwardian Professor Oliver Bulman, at Cambridge University, who described it as “a very sound piece of work” – praise that was almost unknown from the hypercritical old professor. With the award of his PhD, Roger secured a position as Paleozoic paleontologist at the New Zealand Geological Survey in Lower Hutt.

Following his employment at the Geological Survey, Roger continued working on the paleontology of the northwest Nelson area. In 1969 he recruited one of us (JES) as a field assistant and, over 20 subsequent years, unravelled the complex, fascinating geology and paleontology of New Zealand’s oldest rocks. Roger had refined outdoor skills that had been honed by tramping trips as a youth and coaching from the Iban in Borneo. He could make a distinctive rising, Tarzan-like call that would travel great distances in dense bush and, it turns out, proved invaluable for relocating a lost field assistant. He would carefully construct parsimonious fires at lunchtime – just enough to boil the billy and toast the mould from the bread – paying close attention to the choice of firewood, billy pole and toasting fork. In all of this, he used the parang given to him by the Iban in Borneo. On many of the longer field seasons, Roger was accompanied by his now-growing family, who would set up base camp for the summer in the Cobb valley. After long days of geology in the hills and valleys, he would return and help settle children – Alan and Julie – and share stories, play games, and do homework. During one of these field seasons, Roger won a crate of beer in a wager with the Director of the Geological Survey: in the first outcrop he sampled, Roger discovered what are still the only known fossils in a large tract of rocks known as the Greenland Group, a unit that the Director and many other geologists had declared unfossiliferous. As he had done elsewhere in his travels, Roger always did his best to befriend the locals. One such person was Jim Sweeny, a hermit gold miner who lived in a tiny bush hut near Mangarakau. Jim, a self-taught chemist, cultured yeast for his bread from the air and had been jailed as a conscientious objector and pacifist during World War I. His pacifism extended to rodents, which he would live-catch and release on the other side of the creek. On occasion the geologists would stay with Jim for a night or two, careful not to outlast the hermit’s welcome, and Roger would always bring him whisky, cigarettes, and other provisions. All this fieldwork culminated in the publication, in 1979, of a large monograph (amongst many other publications), “Ordovician geology and graptolite faunas of the Aorangi Mine area, north west Nelson, New Zealand” (New Zealand Geological Survey Paleontological Bulletin 47). Forty years later, this publication remains the only comprehensive treatment of the Ordovician and Silurian stratigraphy and paleontology of New Zealand; as things stand, there is no prospect of the work being updated or superseded. His research on these rocks and associated formations also gave Roger key insights into unravelling the complex structure and history of the ancient terranes – building blocks of the crust that have been brought together by continental drift – that make up the oldest parts of the continent Zealandia, and he co-authored the current version of the geological map of the Nelson region.

In 1989, Roger became Chief Paleontologist at the Geological Survey, a role that he held for eight years. Over this period, he successfully managed and mentored about 20 staff through major and sometimes painful structural and funding changes that were occurring in the New Zealand science system, and the transition from the Geological Survey to the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences (now GNS Science). It is sobering and, in these times, somewhat depressing to note that Roger devoted just Friday afternoons to the completion of all administrative duties associated with the role of Chief Paleontologist. Over the same period, for 11 years Roger led one of the large public-good science programmes within the Institute, which undertook a wide range of paleontological research related to geological mapping, resource exploration, climate and environmental change, and geological time scale development. That GNS Science has maintained a strong team of paleontologists doing relevant and cutting-edge research can be attributed, very much, to Roger’s careful stewardship of the group, and this represents a major service contribution to New Zealand science that will have impact well into the future. For those of us who often ate lunch with Roger in the office of the Chief Paleontologist, we remember with fondness his lunchtime tea that he preferred to drink so weak that, some days, he was forced to ask us whether or not he had added tea leaves to the pot. Roger retired from GNS Science in 2002, but maintained an office there and went on to publish another 70 peer-reviewed book chapters and scientific papers, many in highly ranked international journals.

Roger’s scientific legacy spans many areas, and it simply isn’t possible here to give any more than a passing sense of his research contributions. In 1993 he was selected to chair the Cambrian-Ordovician Boundary Working Group of the International Subcommission on Ordovician Stratigraphy, the committee tasked with defining the boundary of this key division of the international geological time scale. The successful prosecution of this contentious and geopolitically charged task – this was no gentle discussion over tea and scones – is testament to Roger’s patience, diplomacy, knowledge, standing, and impartiality. At the same time, he was instrumental in using new quantitative approaches in innovative ways to refine the geological time scale itself, and he is first of two authors on the currently accepted international geological time scale for the Ordovician Period. He brought the same skills to bear on New Zealand’s very own geological time scale – the scale that is used to calibrate the timing of geological events and rates of geological processes that have affected Zealandia. In 2004, under his leadership, a comprehensive and ambitious revision of the New Zealand geological timescale was published (GNS Monograph 22). This is still regarded internationally as the benchmark for regional geological time scales.

Throughout his career, Roger has tackled large questions in evolutionary and paleobiological research, and he has always brought novel insight and clarity of thinking to scientific problems. His early work on graptolites provided a standard for description of these ancient organisms, with collaborators he used them to test models of continental drift, and he was also the first to attempt to use (then) very new, objective techniques to classify the group. With his son, molecular biologist Alan Cooper, he examined the implications of putative mid-Cenozoic (about 25 million years ago) drowning of Zealandia on the development of New Zealand’s unique terrestrial biota; this research subsequently inspired several high-profile research programmes. He then recognised the potential of New Zealand’s remarkable online “Fossil Record File” to investigate questions relating to the controls of marine biodiversity, and he conceived two successful and prestigious Marsden Fund projects on this topic, although he generously encouraged others to take the lead on these. More recently, with Professor Pete Sadler in California, he used the unparalleled fossil history of the graptolites that they developed, together with entirely novel analytical approaches, to generate important new insights into planetary-scale relationships between climate change, geochemical cycles, and evolution and extinction in the marine realm.

Roger received many awards and accolades over his career. To name just a few, he received the McKay hammer of the Geological Society in 1980 for the “most meritorious published work on NZ geology”, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1988, he was awarded a DSc from Victoria University in 1993, and he received the NZ Science and Technology Silver Medal in 2003 and the Hutton Medal in 2017, both from the Royal Society of New Zealand, for “research of outstanding merit”. He received many funding awards to support travel and research overseas, from institutions in New Zealand, Australia, China, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Germany. Foremost amongst these was a prestigious Nuffield Travelling Fellowship, awarded in 1979, that enabled him to spend 15 months at the Natural History Museum, London, and Cambridge University, to pursue his graptolite studies.

Roger is survived by his first wife, Dorothy (Dot) Cooper, his children Alan and Julie, his second wife Robyn Cooper (m. 1991), her children Katrina and Aaron, and grandchildren Meghan, Lauren, Bianca, Torin, Erica, Pierce, Chloe and James.

During one field season in northwest Nelson, whilst hiring motorbikes in the town of Motueka, Roger spied a Penny Farthing leaning against a wall. In no time he had dusted it off and was doing figure-of-eights in the courtyard, before he cycled off down the main street. He brought such levity and humour to all things – his colleagues never saw him angry or upset. His humour shines through the notes that he prepared for his own funeral: “To my family and my friends. If you are listening to this message, it is because I am no longer with you. Sorry about that – I had another appointment that I could not put off … I have never felt that I retired from my work as a research scientist – it has been an abiding interest for me. But now I am retired, properly … in the literal sense. It has been a great life and I have enjoyed it immensely”. With those words, Roger Cooper has now ridden the Penny Farthing off into the sunset.

By James Crampton, Alan Beu, John Simes, Richard Fortey