Matters of coincidence or the collective digital unconscious?

How mapping the digital traces we leave online from expressing ourselves publicly can lead to useful insights – or explain a 'collective digital unconscious'. By Dr Markus Luczak-Roesch, Senior Lecturer from the School of Information Management at Victoria University of Wellington.

We all know situations in which we have a thought coming to our mind and later something happens that is meaningfully linked to that thought but has no causal relationship to it. Most striking examples in this regard are usually dreams that we have from which some events later actually happen in reality. But what do such events - commonly known as coincidences - have to do with filter bubbles, Wikipedia, and citizen scientists hunting for Earth-like planets in the sky?

Coincidences have sparked the interest of scientists many decades ago. Very noteworthy in this regard are the reflections of the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, who coined the term “synchronicity” for “acausal but meaningful coincidences”. Jung argued that observations of synchronicity supported his theory of the collective unconscious - the unconscious that is common to all members of a species or society, stemming from instinct and inherited motifs called archetypes. But Jung’s thoughts were not undebated, in fact, they created and still create some discourse about whether this is a kind of obscure theory of parapsychology or whether there is a fundamental link to our understanding of the mind and even the physics of quantum systems.

Dr Markus Luczak-Roesch

Public information sharing and access at global scale by means of the Internet and the World Wide Web is one of the major achievements of the last 30 years. It is now the norm for many of us to express ourselves publicly by broadcasting articles or messages containing thoughts, opinions, and feelings, by checking in at points of interest, or by spreading photographs of things we find noteworthy.

We can enlist various situations in which this human information sharing contributes to collective problem solving and sense making. Examples include natural disasters or political crises to which a significant amount of people nowadays respond by sending out Twitter messages about situational updates or by updating Wikipedia articles with event-related information in near real-time. But sports events, election campaigns, and online citizen science also fall into that category.

Studying those exemplars shows that, even though there is sometimes a common topic or goal hovering above the information sharing activities of the individuals (e.g. coordinating help in disaster response or optimising travel routes of people being affected by traffic disruptions), people are not necessarily talking with each other or along their social ties, especially when the time to make decisions is limited (e.g. in life threatening situations).

To assist crisis responders but also people involved in urban planning, media reporting, and science, to name just a few, we need an unbiased view of all information that is made available either publicly or through informed consent. Such a view requires data analysis methods that are not tailored to a particular system or case but work on the accumulated information from as many systems as possible. This urges us to protect the decentralisation ethos inherent to the World Wide Web and gives new rise to research on meaningful coincidences.

Looking for activity bursts in information sequences is a proven method that works in this sense. Meaning can be inferred by looking for particular patterns (e.g. a keyword, quote or phrase) that occur at a significantly high rate over certain periods of time in chronologically ordered information sequences.

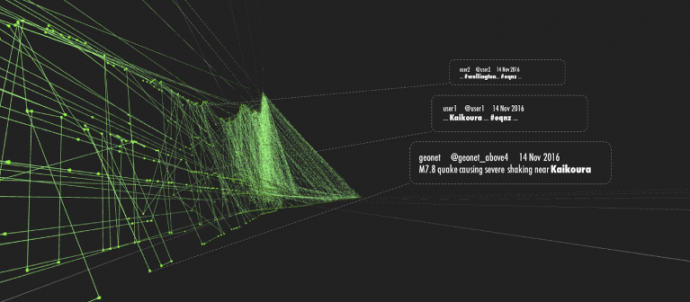

My work on Transcendental Information Cascades expands on the concept of bursts. A Transcendental Information Cascade can be understood as a network view to an information sequence that is originally only ordered by time. Creating this network view allows for tracing the emergence of topics or trends from their initial rising, through activity peaks, until they eventually fade away for some time. And it also allows for mapping how different topics or trends merge and branch over time.

While many people are familiar with the complex structures of social networks, Transcendental Information Cascades represent a novel, formerly hidden dimension of collective behaviour. They confront us with fundamental questions about the notion of time and space in the digital realm.

So far this work has proven useful to map interwoven information sequences on the online citizen science platform Zooniverse and the Wikipedia online encyclopedia. In case of Zooniverse, we found that people developed a unique communication style where relationships by meaning are an essential component of the collective sense making. And our analysis of editing behaviour on Wikipedia revealed links between article revisions and topics that were highly debated in the real-world, such as a same-sex marriage law in the US and a video speech by Edward Snowden at an international conference. In the light of the ongoing public discourse about echo chambers, methods that allow for detecting such hidden links are urgently needed as they can help to trace back potential biases and misinformation.

Expanding our knowledge about Transcendental Information Cascades and our capacities to apply this method can lead to unique insights into the organic structure of the information emission of the human collective that acts and interacts in the digital realm. This can be a key to more effective disaster response or it can help to pop filter bubbles. And to relate this back to C.G. Jung: We may even discover formal properties of a collective digital unconscious.

Further reading:

Kleinberg, J., 2002, July. Bursty and hierarchical structure in streams. In Proceedings of the eighth ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining (pp. 91-101). ACM.

Barabasi, A.L., 2005. The origin of bursts and heavy tails in human dynamics. Nature, 435(7039), pp.207-211.

Luczak-Roesch, M., Tinati, R. and O'Hara, K., 2017. What an entangled Web we weave: An information-centric approach to socio-technical systems. PeerJ Preprints, 5, p.e2789v1.

Tinati, R., Luczak-Roesch, M. and Hall, W., 2016, April. Finding Structure in Wikipedia Edit Activity: An Information Cascade Approach. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference Companion on World Wide Web (pp. 1007-1012). International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee.

Luczak-Roesch, M., Tinati, R., Van Kleek, M. and Shadbolt, N., 2015, August. From coincidence to purposeful flow? properties of transcendental information cascades. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining 2015 (pp. 633-638). ACM.

Published August 2017

This post is from the Past and Future series where, as part of our 150th anniversary celebrations, early career researchers are invited to share discoveries in their fields from days gone by or give us a glimpse into where their research may take us in the future.