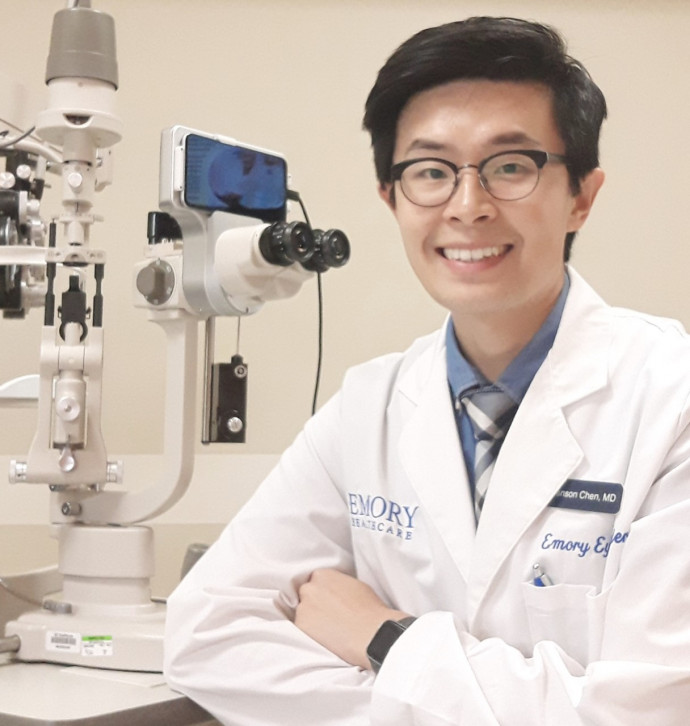

Benson Chen

Benson's involvement with Royal Society Te Apārangi dates back to 2003 when he was a Year 11 student. He now works as a neuro-ophthalmology fellow at Emory Eye Center in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

My relationship with Royal Society Te Apārangi began in 2003 when I was selected to attend the Realise the Dream event in Wellington. I was a Year 11 student at Howick College at the time and had been encouraged by a science teacher to enter a project in the, then, MIT Manukau Science and Technology Fair. Around that time, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) crisis was at its peak. I was particularly interested in the widespread use of facemasks, often not medical-grade, that people were wearing to prevent transmission of the SARS virus. My research project involved assessing the effectiveness of different kinds of facemasks in preventing droplets from passing through. The project did well at the MIT Manukau Science and Technology Fair and I was selected to attend Realise the Dream.

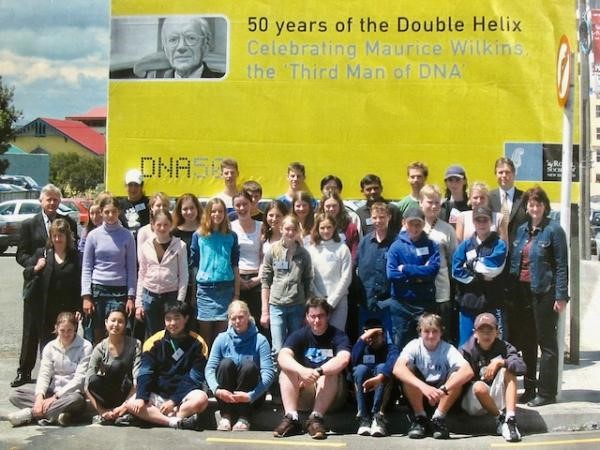

At the inaugural Realise the Dream event in 2003 with other talented students in Wellington.

Realise the Dream was fantastic. The 2003 event was the first Realise the Dream to be held. Myself and 34 other students from around the country stayed in Wellington for one week and attended lectures, visited laboratories and other research institutions, went sight-seeing around Wellington, participated in social activities, and learned how to communicate our scientific ideas effectively. The week culminated in a celebration dinner. Through Realise the Dream I was selected by Royal Society Te Apārangi, with support from Asia New Zealand Foundation, to represent New Zealand at the Beijing Youth Science Creation Competition in 2004.

In my final year of high school in 2006, I was awarded a Gold CREST Award through the CREST programme, supported by Royal Society Te Apārangi. At the time I was interested in how Māori incorporated native flora in their rongoā (traditional Māori healing or medicine). Many native flora have compounds with medicinal properties. For my Gold CREST project, I was interested in researching which plants had the best antiseptic properties and to develop a skin product that incorporated these plants for a client (my mum)! With the help of a facilitator from FutureInTech, I was put in contact with experts in the industry who became my supervisors and mentors. I thoroughly enjoyed the year I spent working on my Gold CREST project in a structured and supported setting. I learned a great deal, particularly about rongoā and the challenges that Māori face with regards to kaitiakitanga and concepts of ‘western’ intellectual property law.

From 2005 onwards, I was invited to assist Realise the Dream annually as an interpreter and support person for the international delegation from Taiwan and China attending the event. It was fantastic being able to support the international participants and enabling them to experience Realise the Dream the way I had experienced it myself two years earlier. I also became involved locally with the Manukau Science and Technology Fair and acted as an Assistant Chief Judge for several years. Most of these activities came to a halt after I began studying medicine at the University of Auckland. Why medicine? At the outset I never really planned a career in medicine, but like many of the opportunities that came along I ran with it and soon figured out that I really enjoyed it. I knew that I wanted a future career that involved science and investigation. However, my Gold CREST project also made me curious about health disparities and how I could use science to help others. Medicine was a natural fit.

Realise the Dream 2009 – student advisors (in hats) with the Taiwanese delegation at Huka Falls.

During medical school I continued to involve myself with any research opportunities that were available. My most memorable project involved looking at the blood supply to the brain and spinal cord under different conditions of circulatory arrest in an animal model, to help answer a clinical question that the cardiothoracic surgeons and anaesthetists had about why patients undergoing a certain type of aorta surgery were not waking up paralysed. And so began my love affair with anything related to neurology and neuroscience. In my final year of medical school, I spent three months in Japan, including eight weeks in Tokyo in the Department of Neurosurgery at the Jikei University Hospital. It was an incredible experience watching the surgeons operate on patients with the use of medical technology and techniques they had developed, as well as the research they were performing to improve their patients’ surgical outcomes.

Medical elective in Tokyo, Japan as a final-year medical student.

After graduating and several years as house surgeon and basic physician trainee in the Auckland region, I embarked on specialist training in neurology. I chose neurology because of my passion for neuroanatomy, and also because it is an intellectually stimulating speciality that requires good old‑fashioned detective work and the ability to think logically (and sometimes outside the box). Many advancements are being made presently within the field of neurology/neuroscience that has led to greater understanding of some neurological conditions (for example the identification of self-recognising antibodies in auto-immune encephalitis) and the development of new and exciting treatments (for example deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease, or immunomodulatory therapy in multiple sclerosis). It is exciting to be riding this wave of research and being able to offer treatments to patients with neurological disorders that were previously untreatable or incurable.

I am currently a neuro-ophthalmology fellow at Emory Eye Center in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, supported by the Neurological Foundation V J Chapman Research Fellowship, which I was awarded in 2018. Neuro-ophthalmologists take care of patients who have visual problems that are related to the nervous system. You may be surprised to learn that we do not see with our eyes, but with our brain! We use almost half our brain for vision-related activities.

I am very fortunate that my mentors in the neuro-ophthalmology unit at Emory Eye Center are not only world‑renowned clinicians, but also well-respected researchers within the field of neuro‑ophthalmology, particularly for Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON), a mitochondrial disorder that affects the optic nerve. Mitochondria act as the power plant of the cell and have their own DNA and inheritance pattern. When they fail to produce enough energy, long-term disorders can arise, resulting in progressive neurological disability such as permanent vision loss. Trials are currently being performed, looking at how we can use gene therapies to treat patients with LHON, and the results are promising.

Living and working in the USA has been fantastic. It is great to be working with like-minded doctors who, like myself, are training and performing research in neuro-ophthalmology. I have also been able to explore other parts of the USA during my fellowship and still have a few places to visit before I return home to New Zealand.

View from the Empire State Building

Looking back at my journey so far, I would not have predicted that I would end up here. The best advice I would give anyone thinking about a career in science or technology is not to feel that you need to make definite plans about what you want to do or achieve. Every opportunity I took led me to more opportunities, some that I never knew existed. I am very grateful for the support I received from Royal Society Te Apārangi early in my journey. The opportunities that flowed from my participation in Realise the Dream through to the skills that I developed in my Gold CREST project, enabled me to realise my dream and establish my career path. My career in medicine has given me the best of both worlds – the ability to conduct research in the field of clinical neurosciences (using the same skills I began to develop as a student), and the ability to apply and translate the findings clinically to the management and care of my patients.