After a specimen has been collected and identified, it may need to be stored, especially if it is a newly described species.

At present New Zealand has 29 taxonomic collections in 20 institutions holding 12 million specimen sets.

Storage requirements and standards

There are very specific requirements for the storage of biological specimens depending on the nature of the taxa being curated.

Such requirements include:

- climate-controlled facilities (e.g. for humidity, temperature, light control; continuous operation of freezers or growth cabinets)

- specific health and safety considerations for material preserved and stored in alcohol or formalin

- storage facilities for specimens that may range from micro-millimetre scales (microalgae, fungi) through to large and heavy objects (marine mammal skeletons, fossils)

- specific maintenance requirements for living collections.

Other important considerations include the management of toxins and hazardous materials associated with the preservation and storage of collections, as well as the requirements under biosecurity legislation for most New Zealand collections to be registered as containment facilities with the Ministry for Primary Industries.

Research

Having access to stored specimens can be really important for research, either taxonomic or for other research questions.

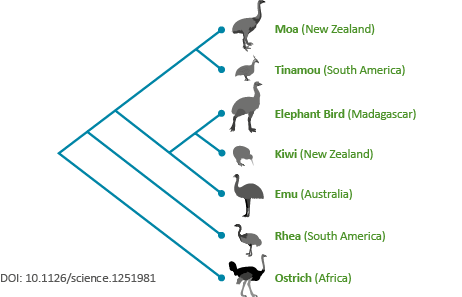

Taxonomy allows the correct identification and naming of species. Nevertheless, names are subject to change as new species are discovered, and existing species are reassessed in the light of new knowledge.

Therefore, in order for the collections to maintain currency and impact, it is essential that they are associated with active taxonomic research programmes. The presence of highly trained and experienced taxonomists is also necessary for informed decision-making by end-users.

Access to appropriate advice and information about new developments within the field, the updating of classifications, and the application of national and international standards are also needed by end-users.

|

Case study: Using herbarium specimens to track the ozone hole Research workers have been able to use herbarium collections of mosses collected from Antarctica to examine flavonoid contents and estimate historical levels of Antarctic UVB radiation. Each year since ca. 1975 an ozone hole has developed over Antarctica from September to late November which means that during spring most of the region is subjected to abnormally high levels of UVB radiation. Using herbarium samples of the moss collected in Antarctica, research workers have been able to compare the levels of flavone aglycones in plants collected before and after the formation of the ozone hole, and thereby determined historical levels of UVB radiation. |

Database

For taxonomic information to be shared, databases need to be maintained and, where possible, made available online.

Databases and information systems

Most of New Zealand’s collections have associated tools and databases, which are the means by which the collections and associated taxonomy are able to be used. These may be institutionally specific (e.g. Landcare Research) or proprietary systems (See Appendix 4). It is important to note that access to data and the quality of subsequent analyses depend on the quality of information available: many collections await identification and taxonomic investigation.

Varying proportions of collections have been databased with many institutions having a considerable backlog of work yet to be completed, but with very limited sources of funds to do so. There is no common standard for collection databases although a bottom-up grouping of institutions has now formed a collaboration seeking to make data available.