Dr Miro Erkintalo

Physicist and self-confessed minimalist, Dr Miro Erkintalo, who takes "tweezers" to laser light, was presented the Hamilton Award in 2016.

From Pori in Finland, Dr Miro Erkintalo came to New Zealand in 2012 after obtaining his PhD in physics. Under the impression that academic careers commence after time spent abroad, it was the opportunity of a post-doc position at the University of Auckland that drew him to Aotearoa. However, it's the people and surrounding environment that has encouraged him to stay.

Now calling Auckland home, Miro is a fan of the outdoors and enjoys getting out and about, which balances with his laboratory work investigating critical interactions between light and matter.

Aiming to answer fundamental questions about nature and technology, Miro researches the physics behind new laser-based systems to see if they can be developed into more efficient technologies that may lead, for instance, to an eco-friendly internet, or higher streaming service speeds.

Identifying as "a bit of an anti-consumerist", Miro chooses to live minimally in support of a more sustainable lifestyle.

Miro's contributions to nonlinear optics and laser physics, particularly for the unification of time and frequency domain models of optical frequency comb generation, was recognised with the 2016 Hamilton Award, Royal Society Te Apārangi's Early Career Research Excellence Award for Science.

Q: What attracted you to New Zealand?

A: There was a clear consensus in my research community that one has to spend some time abroad after completing a PhD to attain an academic career. I had this idea that working for a few years in an English-speaking country would be valuable for a future career, regardless of whether that was academia or industry. That simplified the options somewhat.

I first stumbled on New Zealand through one of my PhD mentors – Professor John Dudley. Although he works in France these days, John is arguably the most famous Kiwi in my field, and is an Honorary Fellow of Royal Society Te Apārangi. In addition, I knew that there are several academics in Auckland with outstanding track records in my field, so I thought that it might be an option. I then met some of those academics at a conference in Germany, and they told me there was a post-doc position open in Auckland. So I applied, got the job, and made the move.

My original plan was to just spend two years working as a post-doc in New Zealand and then shift again. But the people, the climate, and the scenery quickly grew on me, and here I am eight years later, now as a permanent resident.

Q: How do the lifestyles compare?

A: In a thousand different ways. Finns are quiet and private, whilst Kiwis are more relaxed and social, so overall, the lifestyle in New Zealand is more outgoing. The climate probably explains a lot of this: Finnish winter is long and dark whilst New Zealand is "sunny" all year around. That said, because Finnish people take everything a little bit more seriously and they stress a bit more, things like public transport and the quality of housing seem better in Finland.

Finnish people also play ice hockey and race cars. They have no idea what rugby is, and probably think cricket is nothing but an insect. Whereas Kiwis often gather for barbeques, Finnish people like to visit each other’s homes for cinnamon buns and coffee – my recollection is that, per capita, Finns drink more coffee than any other nationality in the world. Finland also has the most heavy metal bands per capita in the world. Maybe it’s the climate and the darkness again, but heavy metal music seems to be a really big thing in Finland, not so much in New Zealand.

And saunas are integral to the Finnish lifestyle. I think the statistics say that there are more than 2 million saunas in Finland, which is a lot for just 5.5 million people.

Q: What do you miss most about Finland?

A: Saunas, proper rye bread, and well-insulated, centrally-heated houses.

Q: Do you have a favourite Kiwi meal?

A: Okay, I had to google for some kiwi meals to answer this question, definitely not “lolly cake”...

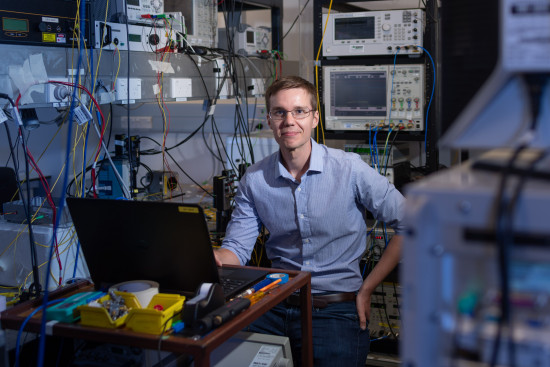

Q: Please describe your research

A: I look at how intense laser light interacts with matter, and try to harness these interactions to either answer fundamental questions about nature, or to develop new technologies. You could say that the overarching aim of my research is to explain the physics of new and emerging laser-based systems so that they can be ultimately used in future applications.

For example, the internet is underpinned by laser light propagating in optical fibres. With more people having access to the internet, and with the popularity of various data-intensive services surging (like for Netflix and other content streaming sites), the amount of information that needs to be carried from 'place A' to 'place B' is constantly increasing. Because of this, there is a continuous need to develop new optical technologies that can make better use of existing networks. Part of my job is to examine the physics that underpin some of these new technologies so that they can eventually deliver us cheaper, faster, and greener internet.

Q: You and your team can “tweeze light”, what does this mean?

A: Imagine two short bursts of light travelling along the same path but are separated from one another by some distance, like two bullets of laser light, one following after the other. A few years ago, we developed a method that allows us to change the relative separation of these two bursts. This is not an easy task, because bursts of light travel at the speed of light (299,792 kilometres per second), and they only last for a millionth of a millionth of a second. However, since the overall gist is a bit like picking up two objects with tweezers and moving them with respect to each other, we coined the term “tweezing of light” to describe our method.

As to how exactly we do this, I’m not sure I can explain that succinctly…

Q: How does information get transmitted through light?

A: Information can be represented in digital form as a binary sequence 'ones and zeros'. For example, the capital letter “A” is typically represented as the sequence 01000001. We can encode such binary information on a laser beam by turning the laser beam on and off. Specifically, if we identify “Laser On” as '1' and “Laser Off” as '0', then the sequence off-on-off-off-off-off-off-on would correspond to 01000001, i.e., the capital letter “A”. This beam propagates at the speed of light, and so transmits the information from one place to another (at the speed of light).

The overall idea is very similar to smoke signals – turning something on and off. The distinct benefit of encoding information on a laser beam, however, is that we can turn the beam on and off very, very quickly – tens of billions of times per second. This means that a laser beam can transmit information very efficiently and at high-speed (billions and billions of 'ones and zeros' per second).

Q: Why laser light?

A: A distinct benefit of laser light is that it can be transmitted through long distances via optical fibres. Since the beam is confined inside the fibre, it won’t be blocked or distorted by any obstacles. Today, submarine optical fibres lay at the bottom of the world’s oceans, connecting different countries to each other. When you send an email to someone overseas, information from your computer is encoded on a laser beam and carried to its destination via optical fibres. Even if you don’t have fibre internet at your home, you can be sure that the data is encoded onto light and coupled into a fibre before it leaves the country. And it’s not just emails, it’s pretty much all internet traffic, as well as long-distance phone calls and cable television. It’s all utilising laser light.

At billions of bits per second, the information carrying capacity of light is far beyond alternative methods. This capacity underpins internet and other forms of long-haul telecommunications, and as such, it underpins our modern information age. If laser-based fibre-optic communications would not exist, we would not have internet as we know it. No Facebook, Twitter, online shopping, Netflix, or any of that.

Q: Are you someone that replaces their devices as soon as a new version is released? Would you line up for the new iPhone?

A: That would be a solid no to both questions. I’m a little bit anti-consumerism to be honest, and only buy things when I really need to. And when I do need to buy something, I buy based on utility, sustainability, and price rather than brand.

Q: Do you find time for yourself being a busy researcher?

A: My lifestyle is pretty minimalistic and disciplined, revolving mostly around work, family, and health. Lots of exercise and healthy home cooking with my partner. I like nature and try to be eco-friendly so that nature likes me back.

I actually rather like my work, so I kind of feel that’s already time for myself. I mean physics is fun! Also, to me “finding time” is just a matter of prioritisation. For example, I always ensure I have time to exercise and cook no matter how busy it is at work.

Q: What do you enjoy doing most when you have spare time?

A: I like being outside and exercising, mostly running. I used to run marathons, but these days I don’t really have enough time to train that seriously. So I just run on my own and with my partner. Just for fun and to stay healthy.

I also love tramping. My partner and I do several multi-day hikes a year, pretty much whenever we find the opportunity.

Q: Do you travel a lot with work? If so, where is your favourite destination?

A: I travel a bit. Between two and four overseas trips per year perhaps. I hope to travel less in the future though so as to reduce my carbon footprint.

Not sure what my favourite place has been. This year I had a conference in Hawaii, which was nice. One thing I’ve noticed is that that, when you live in New Zealand, you don’t really get so impressed by other places anymore. I mean visiting some of the valleys in Hawaii, I couldn’t shake off this feeling that we have much, much nicer ones in New Zealand.

So thinking about it, I guess New Zealand has been the favourite place where I’ve "travelled" for work.

Q: Did you always know you wanted to be a physicist?

A: Not at all. I didn’t really have a clue what to do after high school. Then, when I really had to think about it, I reckoned that physics and maths were always pretty easy for me, and that the problems you get to solve in those subjects are pretty fun. So I decided to go study physics and maths.

Though, even when I was at Uni, I didn’t really know I’d become a physicist. I thought I’d just get an MSc and go work in the technology industry, or else become a teacher. It was only when I was hired as a summer intern at a research lab that I started considering a career in academia as a physicist.

Q: If you couldn’t work in science, what would you do?

A: I’d probably be a writer. I rather enjoy writing (and reading), and think that would be fun as a job. Of course, when you work in academia, you’re already writing quite a lot every day – research articles, grant applications etc. I guess the difference would be writing about fiction rather than facts.

Q: How has winning the Hamilton Award made an impact on your research career?

A: By giving recognition to the work I’ve done in New Zealand, the Hamilton Award has acted as a very valuable catalyst for my research, motivating me to continue doing what I do. Sometimes in academia it takes a long time to see the impact of one’s research, so recognition like the Hamilton Award provide important indication that one is on the right track. Also, the fact that New Zealand is home to a huge amount of exceptionally skilled emerging researchers with very impressive track-records further compounds the significance of this recognition. In addition, I think the Hamilton Award has been very valuable in increasing the visibility of my research in the wider scientific community, which has brought about many beneficial flow-on effects.

About the Hamilton Award

The Hamilton Award, Royal Society Te Apārangi Early Career Research Excellence Award for Science, previously known as the Hamilton Memorial Prize, is awarded annually for the encouragement of early-career researchers currently based in New Zealand for scientific research in New Zealand, and consists of a framed certificate and $2,500.

Miro Erkintalo

Dr

Part of my job is to examine the physics that underpin some of these new technologies so that they can eventually deliver us cheaper, faster, and greener internet.