Research

Published 31 July 2023The olfactory cocktail party: How animals and humans pick out individual smells in a crowd

Dr Tim Edwards (Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato University of Waikato), Dr Paul Szyszka, Dr Mei Peng, and Associate Professor Graham Eyres (Te Whare Wānanga o Otākou University of Otago) are aiming to explore the speed of smell in animals and humans, and whether we use temporal odour patterns to differentiate mixed odours.

While we know how fast our eyes work (processing images at more than 100 frames per second), the speed of our sense of smell is less clear. We usually sniff multiple times to detect a smell, but airborne odours can change rapidly, fluctuating dozens of times per second. Previous research by the team on insects has revealed that the sense of smell is much faster than previously thought, with olfactory receptor neurons responding to odours within less than 2 milliseconds and picking up odour fluctuations at more than 100 times per second.

Paul Szyszka with bees (photo by Mark Hathaway), Tim Edwards with a scent-detection dog, Graham Eyres with Rhododendrons, and Mei Peng with a Snap & Sniff odour testing device.

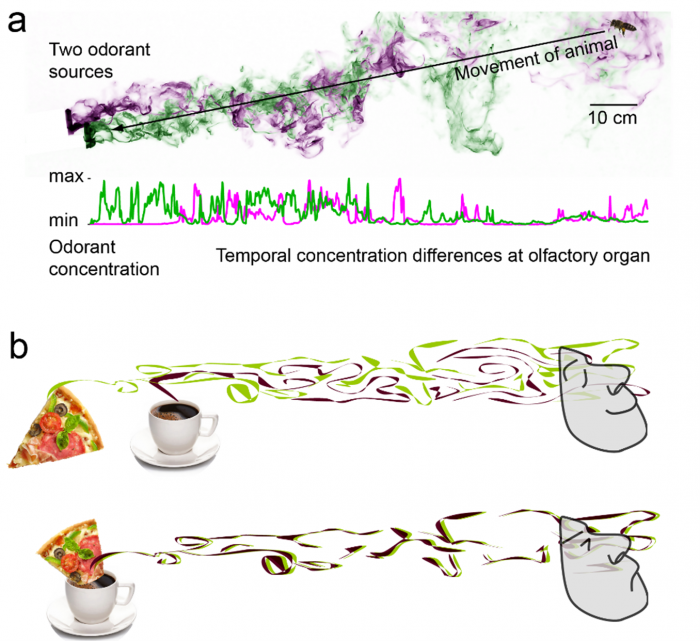

With this new Marsden Fund grant, the team aims to discover if dogs and humans are also capable of fast odour sensing and, if so, how they utilize this ability. In vision and audition, fast sensing is required for separating overlapping objects or sounds, in a process called figure-ground segregation or concurrent source segregation (e.g., we can follow a specific conversation in a noisy room, the so called “cocktail party effect”). The team proposes that fast olfaction could similarly differentiate mixed odours from different sources. This is because odours from the same source arrive at the same time, whereas odours from separate sources have distinct arrival times. If animals can smell fast enough to detect these timing differences in odour arrival, they might have the ability to use this information for perceptual segregation. While the scientist John J Hopfield proposed this hypothesis 30 years ago, it is only recently that supporting evidence in insects has been found by Dr Szyszka's lab.

The temporal structure of odour plumes contains information about the number of odour sources. Figure a) illustrates how wind generates turbulent odour plumes. Plumes from different sources differ in spatial structure, which leads to temporal differences in odour arrival at animals’ olfactory organs. Odour plumes were visualized with smoke and two sequentially shot images were overlaid for illustration. Figure b) illustrates how the temporal structure of two odour plumes (pizza and coffee) helps humans and non-human animals discern whether the odours stem from two separate sources or a single source – the top image has a low correlation between the two odours, while the bottom one has a high correlation.

Three PhD students, Iwan Downie, Dhirendra Singh Gehlot, and Feng-Chun Lin have recently joined the team to contribute to the dog, human, and insect research, respectively. Associate Professor Nathaniel Hall, an expert in canine learning and olfaction from Texas Tech University, has also joined the team in advisory capacity. The team adapted Dr Szyszka's fast olfactory stimulator for use with dogs and humans and are now preparing to test dogs' ability to detect when odours arrive at different times. They are also developing new behavioural paradigms to overcome the problem that animals cannot verbally report what exact odour they are smelling. Using the NZ stonefly, the team discovered that insects' rapid smell sensing is an adaptation for flying, as flying animals encounter faster odorant stimuli than walking animals (publication link: https://doi.org/10.1186%2Fs12862-022-02005-w). The team anticipates that the project's findings could benefit pest control, scent-detection technology, and neurology, including identifying early-stage human disease indicators.

RESEARCHER

Dr Paul Szyszka

ORGANISATION

University of Otago

FUNDING SUPPORT

Marsden Fund

CONTRACT OR PROJECT ID

UOO2114