Research

Published 20 October 2023Setting limits: Rethinking our philosophy of environmental management

With a Marsden Fast-Start grant, Dr Marc Tadaki from the Cawthron Institute has been exploring how limits-based approaches to environmental management are working, and how we can help them work better

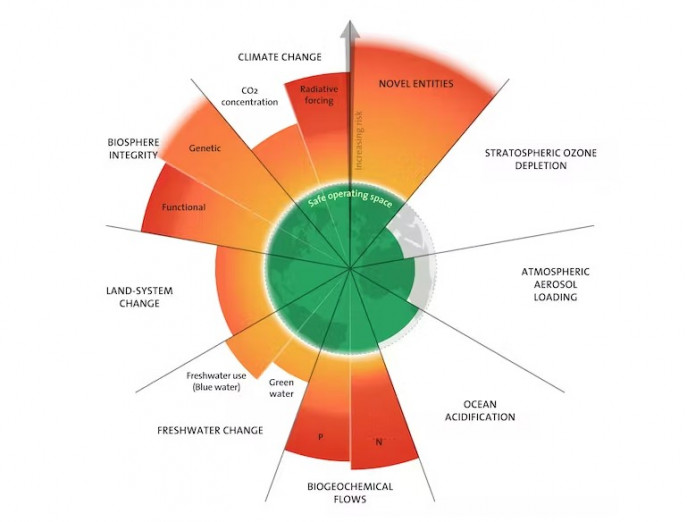

It’s often said in environmental management that “you can’t manage what you don’t measure.” Seemingly straightforward, the logic goes like this: if you care about something in the environment, such as water clarity, nutrient levels, or bug life, you should measure it consistently to understand how it copes in a world impacted by humans. If things aren’t looking good, you can intervene for positive change, setting limits under which such measures must not decline. This idea of governing through ‘environmental limits’ has good support in Aotearoa New Zealand and elsewhere, as we see in repeated international calls for ‘planetary boundaries’ (Figure 1).

Here’s the sum total of our impact on the planet. You can see the areas we’re still within safe limits – and those where we are well past. Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023, CC BY-ND

It seems we may be seeing a new day for environmental management in Aotearoa. The recently passed Natural and Built Environment Act 2023 now requires regional councils to set such environmental limits for air, indigenous biodiversity, coastal water, estuaries, freshwater, and soil. But the question for many remains: will this approach achieve the environmental improvements we desire?

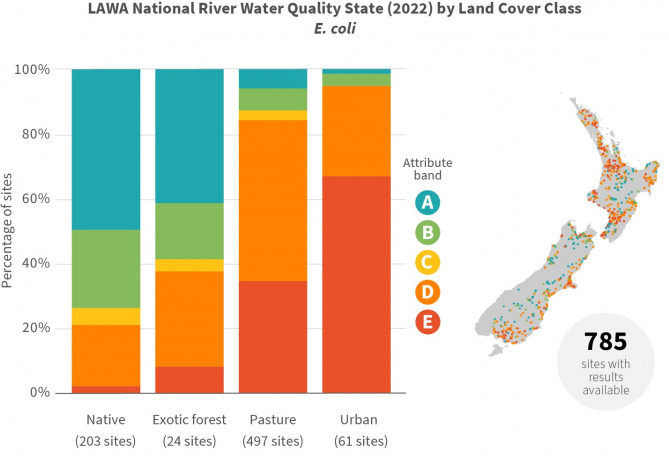

With his Marsden Fast-Start grant, environmental geographer Dr Marc Tadaki has been investigating how a measurement-focused approach to environmental regulation has been playing out across the motu. Since 2014, Aotearoa has been experimenting with limits-based freshwater management, as consecutive government policies required councils to measure and improve upon an initial nine (now 22) measurable characteristics, or ‘attributes’ for rivers and lakes (see E. coli example in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Measurements of river E. coli and their attribute bands across four different land cover classes, for the five-year hydrological period (1 July 2017 – 30 June 2022) at 785 sites. The number of sites with suitable data to determine an attribute band for each land cover class is shown below each bar. The location and attribute band of these monitoring sites is shown on the map. Copyright 2023 by Land, Air, Water, Aotearoa (LAWA). Reprinted with permission.

By looking at how this governance approach creates and uses freshwater knowledge, Dr Tadaki’s research identifies ways to help achieve healthier future ecosystems across Aotearoa. Through interviews with regional council scientists, research scientists, and Māori freshwater practitioners, Dr Tadaki’s research examines how councils are changing what they measure and how they manage their freshwaters, and what challenges they are experiencing.

So far, Dr Tadaki’s research has identified four key issues constraining how this management philosophy might be able to change the world. First, the requirements to measure more are costly, yet resources are scarce. While local governments in theory must measure new environmental attributes, they are constrained by their budgets and by fear of nonelection if they put more pressure on rate-payers to fund extra environmental monitoring. One council, who received a doubling of their river monitoring budget, still had to halve the size of their network because of the massive costs of the new requirements.

Second, while measuring the same attribute across multiple rivers may seem objective, this can mask real differences in environmental quality. It’s possible, for example, for two rivers to show similar phosphorous measurements, however, one may have much more phosphorus laying unmeasured on the riverbed. Consistency, in other words, does not always create comparability.

Third, focusing on time-series monitoring of waterways deprioritises other ways of knowing rivers. For some Māori practitioners and communities, for example, cultural monitoring is more about spiritual connection with the environment than producing high resolution data. As one Māori practitioner expressed, “Indicators: you monitor for resource management. But I don't think that's the primary purpose at all with cultural monitoring. It's not to fit into a framework, it's to connect people and to maintain knowledge, mātauranga, and to pass that knowledge on.” If government agencies only support community monitoring initiatives that produce standardised quantitative outputs, other important spiritual and social values remain underserved. Furthermore, subscribing to only certain types of knowledge also puts limits on what we might imagine or achieve in terms of wellbeing for our rivers.

Fourth, even where we already have high resolution data, this has not necessarily arrested environmental degradation. For example, a decline in freshwater bugs may not be easily attributable to a specific property in a catchment, because every property contributes a little to the problem. Fundamentally, if good existing data have failed to drive improvement in the past, why do we expect that more or newer measurements will produce a different outcome?

Dr Tadaki’s investigation concludes that if the promise of limits-based environmental management is to be realised, our thinking about regulation needs urgent revision and new priorities. To get better outcomes for our ecosystems and our people, environmental practitioners, scientists, policymakers, and advocates should come together and push for solutions that:

- Allow centralised resourcing for councils to monitor and enforce environmental limits, so that these are not constrained by local politics.

- Build place-based understandings of specific rivers using metrics additional to those set by central government.

- Allocate resources and priorities for other ways of knowing freshwater, such as cultural monitoring.

- Empower councils to protect freshwaters by reallocating the burden of proof onto polluters rather than councils.

The world is watching Aotearoa New Zealand‘s development of limits-based environmental management. We may care enough as a nation to measure more, but how we measure, and how measurements influence decisions about land, will determine how well our environments and people fare into the future.

RESEARCHER

Dr Marc Tadaki

ORGANISATION

Cawthron Institute

FUNDING SUPPORT

Marsden Fund

CONTRACT OR PROJECT ID

CAW1901