Research

Published 17 November 2020The 2020 NZ election saw record vote volatility — what does that mean for the next Labour government?

As the dust begins to settle after the 2020 election, a new electoral landscape becomes visible. It is remarkably different from the one before.

First published on The Conversation 20 October 2020

As the dust begins to settle after the 2020 election, a new electoral landscape becomes visible. It is remarkably different from the one before.

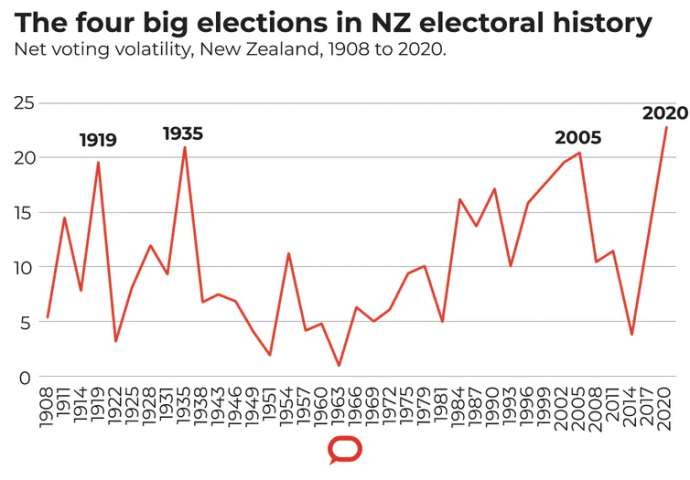

One way to put this in perspective is by measuring what we call “vote volatility” — the net vote shift between parties from one election to the next. By this calculation the 2020 election has ended a period of relative stability.

More significantly, unless reduced after the final count, the net vote shift will be the biggest in over a century.

The challenge will be for Labour to capitalise on this landmark in New Zealand electoral history — before the wheel inevitably turns again.

The first Labour landslide

Vote volatility is calculated by adding the absolute changes in parties’ vote shares between elections, then dividing the sum by two. A score of 0 would mean parties all received the same vote shares as before. A score of 100 would mean a complete replacement of one set of parties by another.

Over the past century, New Zealand has had four elections in which net vote shifts have been well above the norm: 1919, 1935, 2005 and now 2020.

In 1919, the Labour Party broke through into the city electorates and destroyed an embryonic two-party system that had pitched the Reform Party against the Liberal Party at the 1911 and 1914 elections. This turned elections into three-way races, with Labour winning mostly major urban seats, the Liberals doing better in the provincial towns and cities, and Reform in the countryside.

In 1935, in a massive electoral landslide, Michael Joseph Savage’s Labour advanced further, forming its first government. Three conservative parties merged to form the National Party, ushering in New Zealand’s second two-party system.

That lasted much longer, but began to decay as early as the 1950s. At the 1984 election, net vote shifts were higher than at any election since 1938. However, the first-past-the-post system had prevented the emergence of a multi-party system from the 1970s onwards.

The previous biggest vote shift: Michael Joseph Savage (seated third from left) with the first Labour government, 1935-1940. GettyImages

An end to vote stability

An upward vote volatility trend, beginning as long ago as the 1960s, continued after the introduction of MMP. Through the 1996, 1999 and 2002 elections, it reached a peak in 2005. After that, votes moved back in the direction of Labour and National.

As the pattern seemed to persist it led some observers to wonder whether the multi-party politics promised by MMP was a “mirage”.

ACT became a one-seat party, its Epsom electorate strategically gifted from National. New Zealand First dropped out of parliament in 2008, but returned in 2011. Only the Green Party prospered from one election to the next, eating into Labour’s vote share as the party languished in opposition during the John Key years.

Despite the change of government in 2008, vote shifts were modest, a pattern repeated in 2011. Indeed, in 2014 net vote shifts were the second lowest of any election over the previous century, only slightly higher than those of the “no change” election of 1963.

In 2017, Jacinda Ardern’s Labour took office, reflecting a real shift to the left, but relying on New Zealand First’s coalition choice more than the movement of votes (which was not enough for a left majority). It seemed party politics under MMP had stabilised after a brief period of experimentation that ended after the 2005 election.

The 2020 election breaks the mould. If the pattern holds after the counting of special votes, it will surpass even 1935, New Zealand’s hitherto most dramatic realigning election.

Moreover, turnout was up, another indicator of a big change. This was despite a widely predicted Labour win and a big margin between Labour and National in pre-election polls — expectation of a decisive result usually pulls turnout down.

Landslide: Prime Minister-elect Jacinda Ardern with senior party members, the day after their historic election win. GettyImages

The challenge to create a legacy

One might dismiss this as a one-off. COVID-19 and the government response created a perfect storm. When the crisis is over, things will return to normal.

But one could have said the same thing in 1935. The depression of the 1930s gave Labour the chance to win. Even if the economic recovery that followed was only partly an effect of Labour policy, the party reaped the rewards in 1938.

Like Michael Joseph Savage before her, Jacinda Ardern has demonstrated the leadership demanded by the times. But there is a difference. Labour in 1935 came to power with a big promise of a welfare state. Labour in 2020 has made no big promises, although many smaller ones. It faces huge challenges, arguably much more demanding than those of the 1930s.

COVID-19 and a sustainable economic recovery will be the first priorities. Climate change, increased international tension, trade wars, internal cultural diversity and working through ongoing responsibilities under the Treaty of Waitangi — all of these will test the mettle of the Ardern government.

The 2020 election tells us the New Zealand party system is more prone to big shifts than expected after 2005. Periods of apparent two-party dominance may be temporary. Both Labour and National are prone to rise and fall, creating space for smaller parties to step into the gaps as they open, and fall back as they close.

The catalysts of change may be big external shocks or internal challenges. All else being equal, the 2020 election is likely to herald a period of Labour dominance, but eventually the tide will turn. Labour’s biggest challenge will be to establish a lasting policy legacy before that happens.

Additional information: The Conversation Article

RESEARCHER

Jack Vowles

ORGANISATION

Victoria University of Wellington

FUNDING SUPPORT

Marsden Fund

CONTRACT OR PROJECT ID

VUW1624