News

Published 19 September 2018The sometime chieftainess

'The Old Time Māori' is part of Te Takarangi 150 Māori authored book series and was penned by the eminent Makereti Maggie Papakura. An enigma of 19th century London society, Makereti enthralled the public both as an entertainer and performer, but also made a significant contribution to academia as the first Māori scholar to publish an ethnographic account of Māori life.

Well known New Zealand women of the early 1900’s include the writer Katherine Mansfield, and the leader of women’s suffrage in Aotearoa, Kate Sheppard. Kate’s portrait now graces the New Zealand ten-dollar note, along side a white camellia.

The camellia is our symbol for women’s suffrage and was given to members of Parliament who supported the suffrage bill, which passed on 19 September 1893 and would give women the right to vote. New Zealand became the first self-governing country in the world to give women the right to vote in parliamentary elections, with the petition seeking the right to vote being signed by nearly one in four women in Aotearoa.

Today on the 125th anniversary of women’s voting rights, 19 September 2018, and in the wake of Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori (Māori language week), we celebrate another strong female of the early 1900's: ethnographer, entertainer and international darling of the press, Makereti.

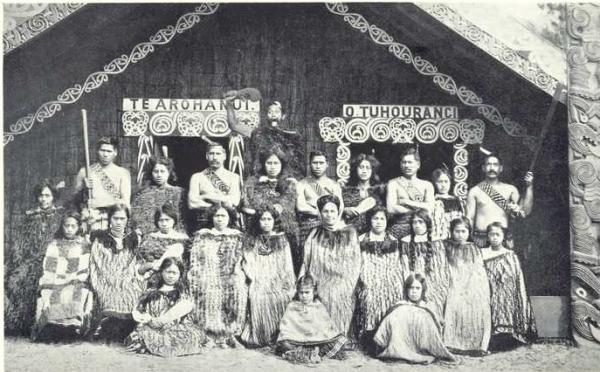

Makareti with members of her kainga at Whakarewarewa

From the small village of Whakarewarewa near Rotorua, Makereti was born on 20 October 1872 under the name Maggie Thom. The daughter of the highly-born Pia Ngarotu Te Rihi (Te Arawa) and Englishman William Thom, soon after her birth Maggie was taken and raised by two of her relatives. Marara Marotaua and Maihi Te Kakau Paraoa, her mother's paternal aunt and uncle, who deeply immersed Maggie in the traditional culture and knowledge of the Māori people for the first ten years of her childhood.

During this time Maggie learnt about genealogy, star patterns, bird calls, the secrets of the land, forests and lakes around her, as well as to hunt and harvest in the ancient ways of her tīpuna. This early learning meant Maggie developed a great understanding of Te Ao Māori, the Māori knowledge system and day-to-day lifestyle that was already under threat.

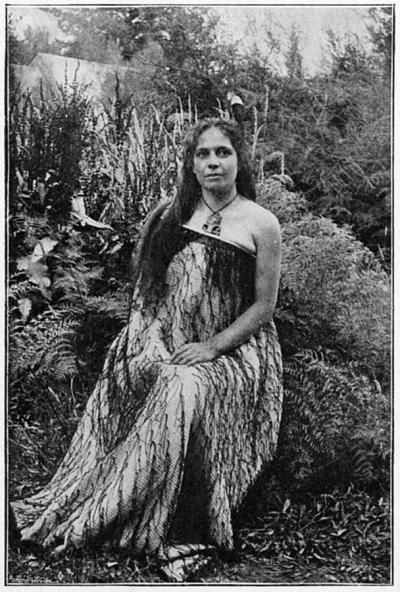

After her school years in Napier, Makereti returned to Whakarewarewa as a teenager. She then spent time as a guide to wealthy tourists in the bustling Rotorua township. Her eloquent language skills, flair and beauty helped cement Makereti’s resounding popularity as a tour guide.

Historic anecdotes tell that whilst guiding a small group of overseas visitors around the geothermal wonders of the Whakarewarewa Valley, the tourists paused next to a frothing spout of the active Papakura Geyser and demanded Maggie tell them her ‘real name’, her ‘native’ name, as surely Maggie Thom could not be it?

As spray from the geyser boldly bounced out beside them, “My name is Papakura. Maggie Papakura” Maggie replied, without hesitation. And so the historic tale goes, this is how Maggie named herself and gradually renamed her family.

The Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York were hosted by Makereti in 1901 to a crowd of thousands, after which Maggie shot to international fame as the most fashionable and sought-after guide in Aotearoa. Maggie published a self-titled handbook Maggie’s Guide to the Hot Lakes and began jet setting between Australia and New Zealand. Wherever she went she entranced the local society, and was often featured in newspapers and magazines.

Makereti used her powerful social influence to advocate for her people’s right to fish, hunt and snare on their ancestral land and she publicly condemned the desecration of Māori burial grounds by grave robbers.

The pivotal moment in Makereti’s life came when she put together a Māori cultural party of 40 top performers and entertainers to travel to London for the Festival of Empire celebrations. The impressive gathering featured delegations of indigenous peoples from all over the British Empire in celebration of coronation of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, who had been so captivated with Makereti several years earlier in Rotorua.

Makereti’s delegation featured heavily in the press, with the public expressing great excitement and wonderment at the artefacts that they had brought with them, including a Māori house and pātaka (raised storehouse on stilts). Makereti ended up marrying the wealthy Oxford landowner Richard Staples-Browne and became the mistress of Oddington Grange. She travelled extensively throughout Scandinavia, Europe and Asia before she began her academic endeavours into the new field of anthropology.

The largest room in her home at Oddington Grange was known as the ‘New Zealand Room’ and Makerita decorated it with carvings, cloaks and glass-show case of huia birds. The room became a treasure trove of Māori cultural artefacts and a place for Makereti to hold lectures and disseminate her knowledge.

Makereti conferred closely with her kuia and koroua about what information she ought to divulge and what to withhold. She was conscious of the significance of tapu and always ensured that her writings were published with the blessings of her people.

She assisted many ethnographers with their work, though her contributions were rarely acknowledged. Makereti was well aware of this and her frustration at the constant misrepresentations these ethnographers were portraying in their books is seen in her scathing comments in The Old Time Māori of the "outrageous untruths of ignorant writers".

Makereti's work The Old Time Māori was intended as an antidote to remedy these untruths, though she died of a sudden heart attack just one month before she was due to present her thesis. Makereti had finished the first draft of the manuscript, and the work was published 8 years after her death through the efforts of T.K Penniman.

The Old Time Māori is featured in Te Takarangi series of 150 Māori authored books, which is presented in partnership by Royal Society Te Apārangi with Ngā Pae O Te Māramatanga. The Old Time Māori is the first comprehensive ethnographic account by a Māori scholar, yet it faded into obscurity alongside accounts that were published by Pākehā men like Best and Cowan.

Emeritus Professor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku (Te Arawa, Tūhoe) looks at several reasons in her introductory chapter of The Old Time Māori as to why these books have long been overlooked. She suggests that perhaps the shadow cast by World War II simply overwhelmed it, as happened to much scholarly works of the time.

Emeritus Professor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku

Or perhaps its relative obscurity was due to the fact The Old Time Māori did not stem from a migrant historian encamped within New Zealand sending pages of their personal observations back to England, but instead from within the decidedly un-exotic Oxford itself, and even more unusually - from the pen of a Māori woman who "should have known her place".

Professor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku is also a featured author in Te Takarangi with her book Mau Moko. She received the Royal Society Te Apārangi's Pou Aronui Award in 2017 for her work blazing a path for indigenous culture, heritage and feminist scholarship.

Ngahuia ends this introductory chapter by simply saying "A solitary female voice in a bleak wilderness of male scholarship, the work of an isolated indigène amidst the clattering weight of western colonialism, Makereti's ethnography offers a rare vision of community and culture - unprecedented and unmatched even to this day. I celebrate this reprinting, for Māori women, for the Māori people, and most of all, for Makereti herself"